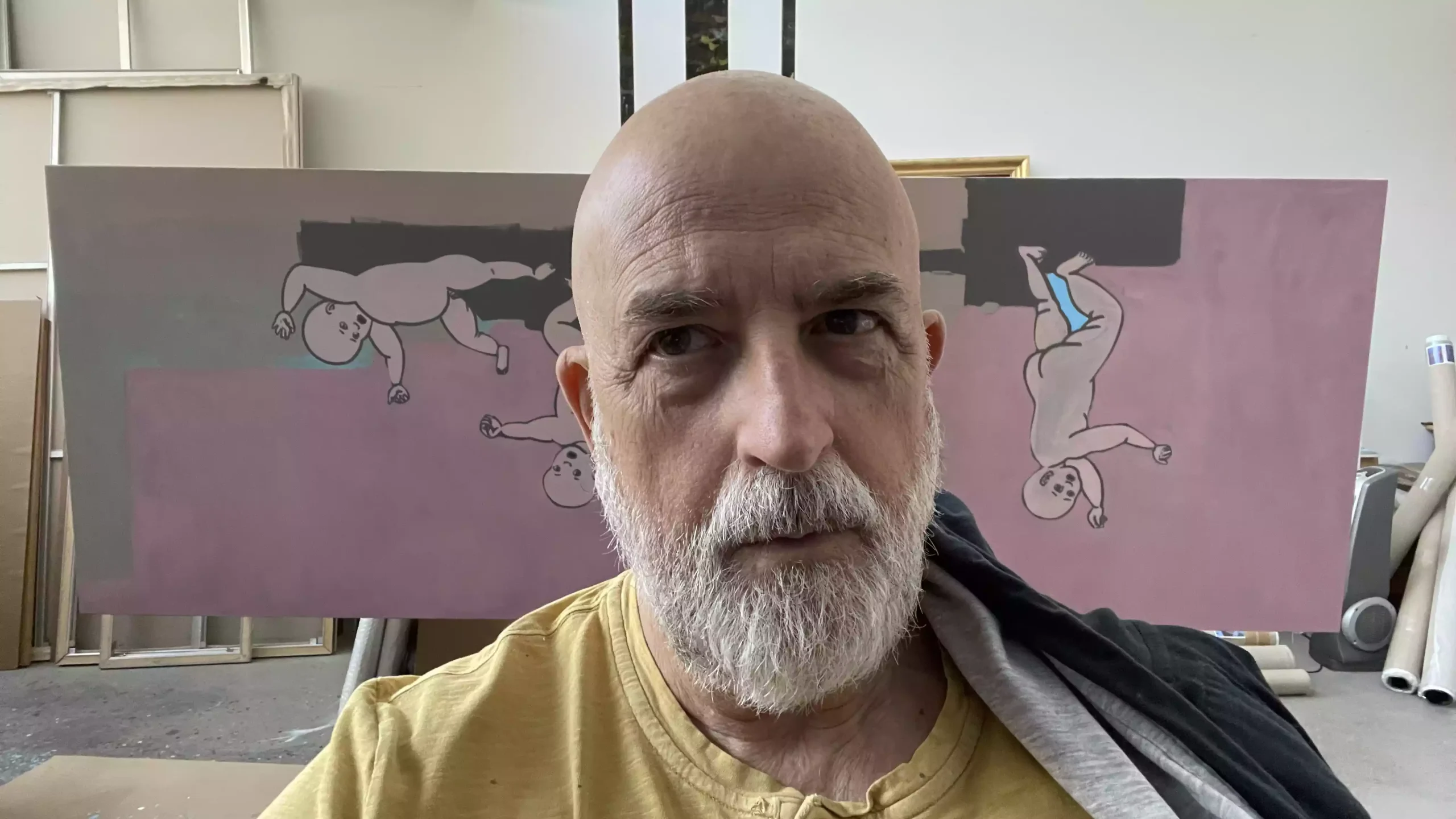

Hubert Schmalix

During the confrontational 1980s, a period when young artists around the globe began to fervently revive painting, Hubert Schmalix emerged at the forefront of this vibrant resurgence. Characterized by an expressive blend of poetry, storytelling, eruptive emotion, and subjective experience, these artists, labeled "Junge Wilde," gave rise to what was known internationally as "New Painting," "Transavanguardia," or "Bad Painting."

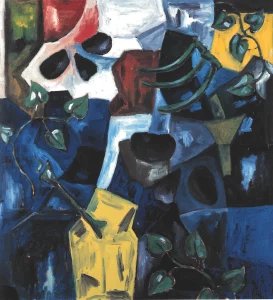

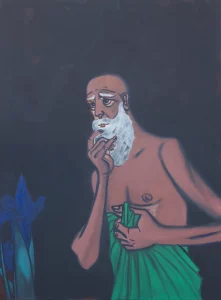

During the confrontational 1980s, a period when young artists around the globe began to fervently revive painting, Hubert Schmalix emerged at the forefront of this vibrant resurgence. Characterized by an expressive blend of poetry, storytelling, eruptive emotion, and subjective experience, these artists, labeled "Junge Wilde," gave rise to what was known internationally as "New Painting," "Transavanguardia," or "Bad Painting."  For Schmalix, dedicating himself to arguably art’s most traditional medium in this provocative era had a distinctly subversive quality.Mass media, cinema, pop music, fashion, and art history formed the eclectic reservoir from which youthful passion drew its strength. In this pivotal historical moment, painting became a bridge, linking its storied past to an emergent digital image explosion—effectively connecting history with a futuristic vision. Experiencing the future as it unfolds from the past within the present creates a conceptual paradox, a compelling interplay between representation and abstraction. Schmalix’s nudes frequently inhabit monochromatic color fields, transforming abstraction into narratives.

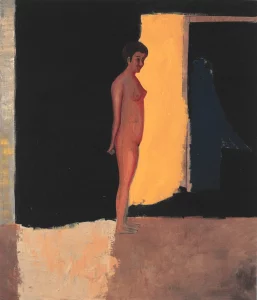

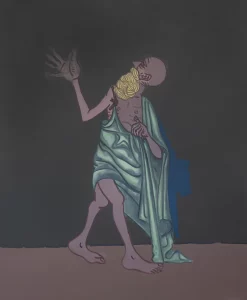

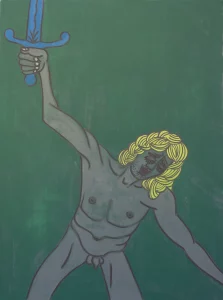

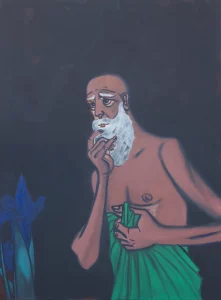

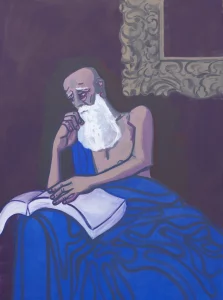

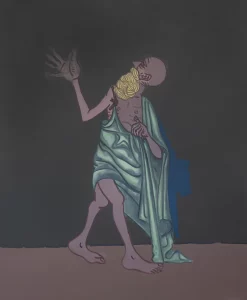

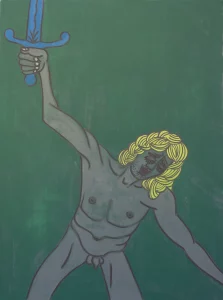

For Schmalix, dedicating himself to arguably art’s most traditional medium in this provocative era had a distinctly subversive quality.Mass media, cinema, pop music, fashion, and art history formed the eclectic reservoir from which youthful passion drew its strength. In this pivotal historical moment, painting became a bridge, linking its storied past to an emergent digital image explosion—effectively connecting history with a futuristic vision. Experiencing the future as it unfolds from the past within the present creates a conceptual paradox, a compelling interplay between representation and abstraction. Schmalix’s nudes frequently inhabit monochromatic color fields, transforming abstraction into narratives.  Familiar imagery emerges—nudes, Christ figures, a house, a landscape—each appearing familiar to us as though borrowed from other visual contexts.

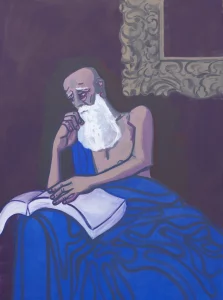

Familiar imagery emerges—nudes, Christ figures, a house, a landscape—each appearing familiar to us as though borrowed from other visual contexts.

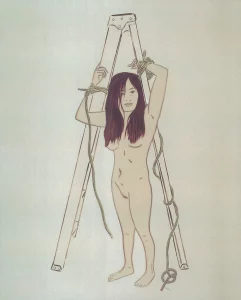

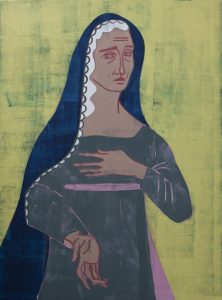

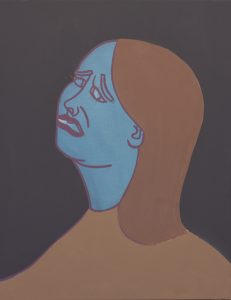

To this day, Schmalix’s paintings exude a remarkable ease and cool detachment that simultaneously provoke subtle unease. The figures he portrays often seem uncertain, questioning their belonging or whether their surroundings truly match them, as if pictorial elements possess an inherent self-awareness. Echoing philosopher Jean-François Lyotard: "It should finally be clear to us that our role is not to deliver reality, but rather to invent allusions to conceivable thoughts that cannot be directly depicted." Schmalix's pictorial elements are unmistakably clear—a tree is undeniably a tree; the nude woman standing awkwardly next to a ladder is unambiguously visible. Yet this clarity is deceptive, with a hidden narrative quietly unsettling us, prompting contemplation: What story lies behind the restrained woman and the ladder beside her?  Sexual undertones in Schmalix's work remain neutral, dispassionate, ordinary, and devoid of sinful awareness—they are simply images.

Sexual undertones in Schmalix's work remain neutral, dispassionate, ordinary, and devoid of sinful awareness—they are simply images.

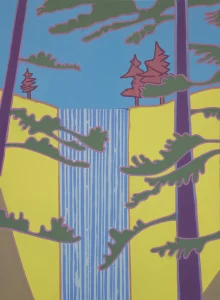

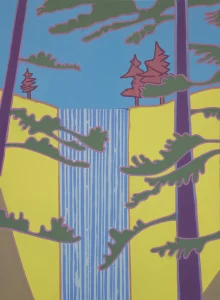

David Hockney, by contrast, envisioned a sensual paradise he believed he'd discovered in California. Schmalix’s vision is more tempered, more detached. His vividly colored landscapes—featuring blue trees, purple skies, and orange rivers—may appear idyllic, yet they do not represent Arcadia.

Walt Disney offered millions of children a paradise; Schmalix subtly references the atmosphere of comics, blending elements reminiscent of Art Deco and Jugendstil into his paintings.

Yet, the mood within these vibrant canvases can shift unexpectedly, engaging the viewer's visual consciousness. As we now understand, even pollution can give rivers appealing colors. Thus, Schmalix’s landscapes are not paradisiacal realms we wish to inhabit, but evocative visions, shaped by longing.

The Mediterranean-born European artist found in California an ideal environment, vibrant under the gleaming Pacific sunlight. The same might be said about the artworks he produced during his time in Los Angeles.

These paintings convey a relaxed emptiness paired with enigmatic, subtly emerging narratives. Themes of belonging and isolation, abundance and emptiness intertwine, sometimes subtly reflected in the gazes of his depicted figures. Schmalix’s use of flat color planes echoes the aesthetic of screen-printing, balancing glamorous pop appeal with the functional simplicity reminiscent of sign painting.

Hubert Schmalix paints with the profound awareness that painting has existed long before his time. Yet, rather than abandoning the medium due to conceptual considerations, he passionately embraces painting precisely because of this rich historical consciousness.

Hubert Schmalix

During the confrontational 1980s, a period when young artists around the globe began to fervently revive painting, Hubert Schmalix emerged at the forefront of this vibrant resurgence. Characterized by an expressive blend of poetry, storytelling, eruptive emotion, and subjective experience, these artists, labeled "Junge Wilde," gave rise to what was known internationally as "New Painting," "Transavanguardia," or "Bad Painting."

For Schmalix, dedicating himself to arguably art’s most traditional medium in this provocative era had a distinctly subversive quality.Mass media, cinema, pop music, fashion, and art history formed the eclectic reservoir from which youthful passion drew its strength. In this pivotal historical moment, painting became a bridge, linking its storied past to an emergent digital image explosion—effectively connecting history with a futuristic vision. Experiencing the future as it unfolds from the past within the present creates a conceptual paradox, a compelling interplay between representation and abstraction. Schmalix’s nudes frequently inhabit monochromatic color fields, transforming abstraction into narratives.

Familiar imagery emerges—nudes, Christ figures, a house, a landscape—each appearing familiar to us as though borrowed from other visual contexts.

To this day, Schmalix’s paintings exude a remarkable ease and cool detachment that simultaneously provoke subtle unease. The figures he portrays often seem uncertain, questioning their belonging or whether their surroundings truly match them, as if pictorial elements possess an inherent self-awareness. Echoing philosopher Jean-François Lyotard: "It should finally be clear to us that our role is not to deliver reality, but rather to invent allusions to conceivable thoughts that cannot be directly depicted." Schmalix's pictorial elements are unmistakably clear—a tree is undeniably a tree; the nude woman standing awkwardly next to a ladder is unambiguously visible. Yet this clarity is deceptive, with a hidden narrative quietly unsettling us, prompting contemplation: What story lies behind the restrained woman and the ladder beside her?

Sexual undertones in Schmalix's work remain neutral, dispassionate, ordinary, and devoid of sinful awareness—they are simply images.

David Hockney, by contrast, envisioned a sensual paradise he believed he'd discovered in California. Schmalix’s vision is more tempered, more detached. His vividly colored landscapes—featuring blue trees, purple skies, and orange rivers—may appear idyllic, yet they do not represent Arcadia.

Walt Disney offered millions of children a paradise; Schmalix subtly references the atmosphere of comics, blending elements reminiscent of Art Deco and Jugendstil into his paintings.

Yet, the mood within these vibrant canvases can shift unexpectedly, engaging the viewer's visual consciousness. As we now understand, even pollution can give rivers appealing colors. Thus, Schmalix’s landscapes are not paradisiacal realms we wish to inhabit, but evocative visions, shaped by longing.

The Mediterranean-born European artist found in California an ideal environment, vibrant under the gleaming Pacific sunlight. The same might be said about the artworks he produced during his time in Los Angeles.

These paintings convey a relaxed emptiness paired with enigmatic, subtly emerging narratives. Themes of belonging and isolation, abundance and emptiness intertwine, sometimes subtly reflected in the gazes of his depicted figures. Schmalix’s use of flat color planes echoes the aesthetic of screen-printing, balancing glamorous pop appeal with the functional simplicity reminiscent of sign painting.

Hubert Schmalix paints with the profound awareness that painting has existed long before his time. Yet, rather than abandoning the medium due to conceptual considerations, he passionately embraces painting precisely because of this rich historical consciousness.

Works

Landscape, „Poor House“

2019 Oil on Paper 130 x 100 cm

All Mine

2019 Oil/linen 175 x 130 cm

Flowers, „Listen“

2022 Oil/linen 175 x 130 cm

Landscape, „Messed Up Landscape“

2024 Oil/linen 100 x 80 cm

Sydney

2022 Oil/linen 90 x 70 cm

Figure, „Idiot, small, 2“

2024 Oil/linen 100 x 80 cm

2021_LA_175x130_1648

LA_2018_90x400_0741

2021_LA_175x130_1645

2021_LA_175x130_1644

2021_LA_175X130_1569

LA_2018_90x400_0739

LA_2018175x130_0681

LA_2022_345x500_1750

LA_2022_300x245_1755

LA_2022_245x500_1748

LA_2018_70x175_0799

LA_2021_245x200_1640

LA_2021_175x130_1722

LA_2018_70x175_0733

LA_2021_175x130_1688

LA_2021_175x130_1687

LA_2018_70x175_0798

LA_2021_175x130_1677

LA_2021_175x130_1631

LA_2021_70x175_1734

LA_2018_175x130_0796

LA_2021_175x130_1675 2

LA_2018_70x175_0732

2021_LA_175x130_1655

2021_LA_175x130_1652

2021_LA_175x130_1649

BOUNTY

2016 Oil/linen 175 x 130 cm

2021_LA_175x130_1648

LA_2018_90x400_0741

2021_LA_175x130_1645

2021_LA_175x130_1644

2021_LA_175X130_1569

LA_2018_90x400_0739

LA_2018175x130_0681

LA_2022_345x500_1750

LA_2022_300x245_1755

LA_2022_245x500_1748

LA_2018_70x175_0799

LA_2021_245x200_1640

LA_2021_175x130_1722

LA_2018_70x175_0733

LA_2021_175x130_1688

LA_2021_175x130_1687

LA_2018_70x175_0798

LA_2021_175x130_1677

LA_2021_175x130_1631

LA_2021_70x175_1734

LA_2018_175x130_0796

LA_2021_175x130_1675 2

LA_2018_70x175_0732

2021_LA_175x130_1655

2021_LA_175x130_1652